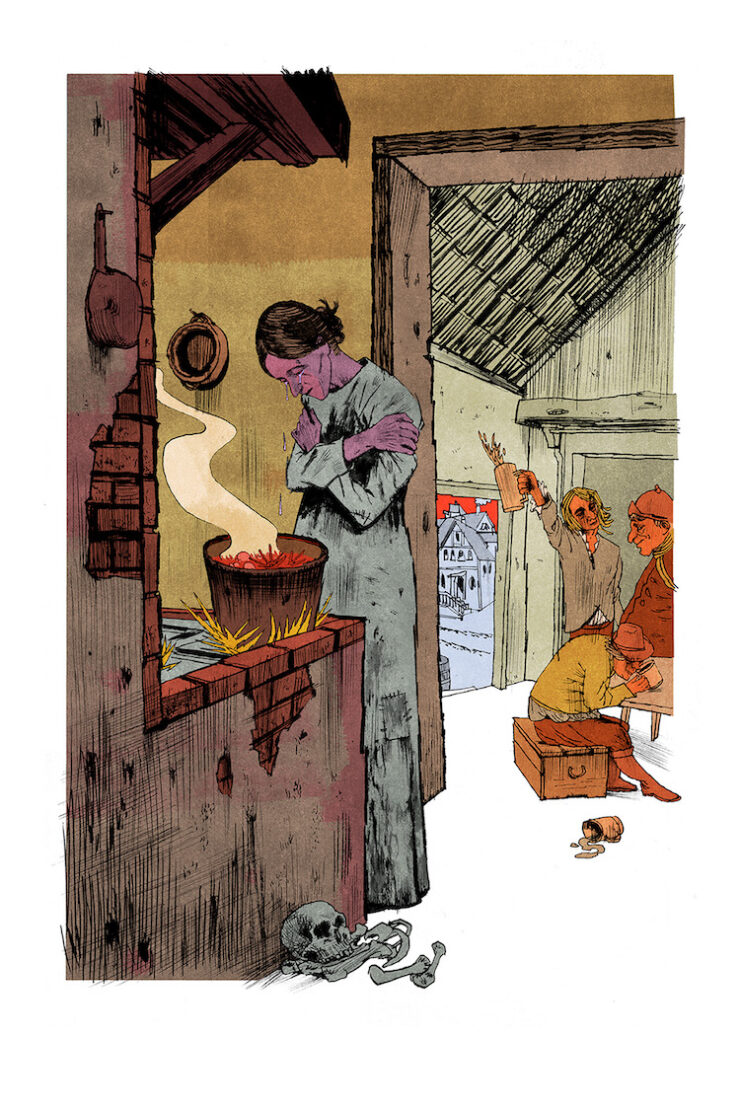

Kell Woods returns to the world of her bestselling novel, After the Forest, weaving a dark and lyrical standalone, spoiler-free backstory for a young witch at the siege of Breisach, years before she became notorious for her gingerbread cottage…and her appetite.

Author’s Note: This story contains descriptions of domestic violence, sexual assault, animal harm, and cannibalism.

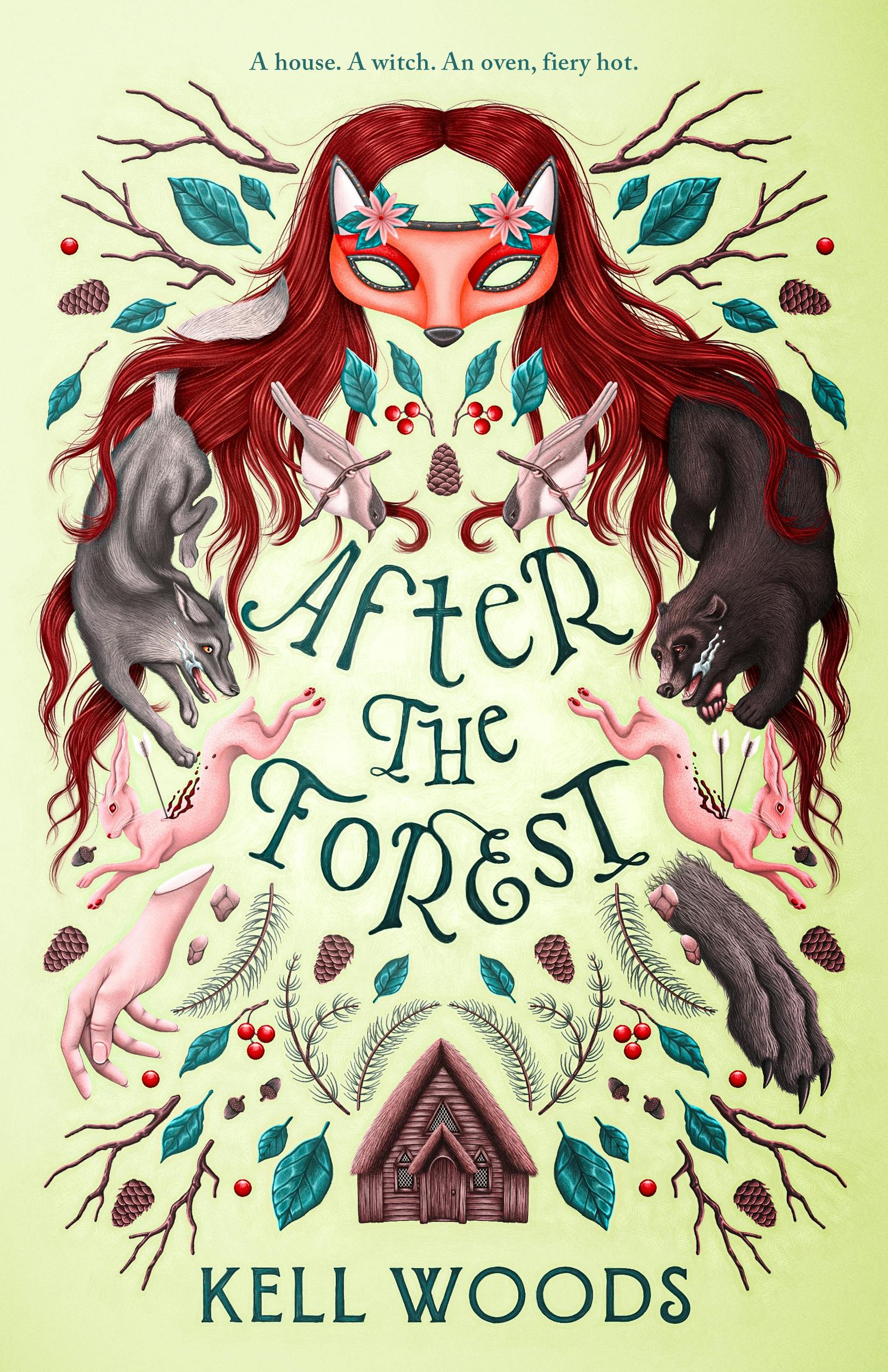

After the Forest is available now in hardcover wherever books are sold, or pre-order the trade paperback edition, available everywhere on August 27th, 2024!

Junia remembered the beginning of the war without end. A comet had appeared in the skies above the Holy Roman Empire, a blaze of flame burning a path across the heavens for a month. By the time it had disappeared, Junia’s mother and father had succumbed to the plague and she had left their small village on the Rhine to live in Breisach with Uncle Johannes and Cord. Panic at the comet’s appearance, its meaning, ran high. The priests believed the comet foretold of evils to come. That God had sent it as a warning to the people to mend their ungodly ways: pride, swearing, fornication. Disobedience, greed and its lover gluttony. Witchcraft. They warned that God would punish them all if they did not repent.

Woe the great sinfulness.

Ten years old and grieving, Junia paid little heed to the sermons she attended with Uncle Johannes in St. Stephan’s. Wasn’t she being punished already? Hadn’t God taken not one, but both her parents? As the years passed and the war that had sparked in the comet’s wake blazed across the land, she came to realize that she had been wrong. Her punishment, all their punishments, had not even begun.

Cord had cared for her at first. She was sure of it. Beating away the other children when they were cruel. Orphan. Waif. Sliding the best piece of ham to her under the supper table in a greasy fist. Wicked grin; the best of him. Yet over the years her cousin had twisted, somehow. His body was strong and sturdy, but inside he was as gnarled and crooked as the old juniper tree in the courtyard, the tavern’s namesake. Hard to say when it started. Was it when Junia’s body began to change? Buds blooming spring-sweet on her chest, apple-round hips? She supposed she had been beautiful, then. Certainly Uncle Johannes had kept a careful eye on her when she helped him in the tavern, clearing the empty plates and wiping the tables of scraps and spills, the occasional splash of vomit. Noting the way his customers watched her, the heavy look in their eyes. Sharp man, Uncle Johannes. Ran a tight business. Clean tables, good food. None of the fighting and dancing and groping in shadowy corners you’d find in some of the rougher establishments in the Fischerhalde. Junia had never once seen him share a glass of cherry-water or wine with his customers. The kitchen would be better for you, Junia, he had said, those little creases of worry showing between his peppery brows. Safer for you there, mein Liebster.

So she had gone to the kitchen, helped the cook prepare the dough for Knöpfle, squeezing its pale softness through the old noodle press, tossing it into the pot to boil. She had sliced the ham and cheeses, learned to bake butterbrezel and gingerbread. Turned out she was good at it, had a knack for throwing flour and salt and water in a bowl and lifting something wondrous out in its place. She had been happy, for a time. Until, when she was sixteen, Uncle Johannes died, leaving the Juniper Tree, and Junia, in Cord’s hands.

Her cousin was not like his father. None of that calm, that wizened strength. Uncle Johannes maintained order with a glance, or a quiet word. Cord was all shoulders and fists, a storm rolling in from the Schwarzwald, blustering over the Rhine.

Junia continued to work alongside the cook in the kitchen. Without Uncle Johannes’s presence, the customers grew bold, contriving ways to find her there. They would lean in the doorway, watching her work, or smiling when she stole scraps for the little tavern cat that was supposed to be catching mice, but was always at Junia’s heels. Lazy, speculative smiles. What they wouldn’t do, those smiles said, to get Junia into a shadowy corner. Catch her like a mouse. There were kind smiles, too, sometimes. Customers who talked instead of stared, who were interested in the thoughts and feelings beneath Junia’s bodice and skirts. Hardly mattered. Cord had beaten away any man who had come sniffing. Filthy fucking foxes on the rut. I won’t let them touch you, Junia, he promised. Won’t let anyone hurt my sweet cousin. After all, there’s just the two of us now.

Just the two of us now.

She thought of that, over and over, when he crept down the hallway that night and into her bed, covering her mouth with his hand. When he slid between her legs.

Filthy fucking foxes.

Things got worse when the first of the little ones came along. Junia knew Cord had kindled one in her when her monthly bleeding stopped, when she was so wretched and sick in the winter mornings that she’d hurry from her room above the tavern—quiet now, don’t wake Cord—and, feet freezing-bare, throw her guts up in the snow.

Only apples soothed her roiling belly. One morning, when the heaving and sweating and clinging to the juniper tree was done and the bile still steamed at her feet, she peeled one. Too hasty. The knife sliced into her hand. Blood spattered the snow. One drop, two drops, three.

Bad sign, that blood. No good would come of it.

Marriage, Cord had announced when Junia could no longer hide her swelling belly. It is the best, the only option.

Junia hesitated. By now she had learned that there were two Cords. There was the Cord she had known her whole life—greasy-ham grin and kindness—and the other Cord. This other version was not her cousin. It was as though the Devil himself, the Evil One, took hold of his body. It happened in the deeps of the night, usually, or when he’d drunk too much. At other times, too, when Junia least expected it.

Hard to say which one of the two regarded her now. She opened her mouth, preparing to deliver the words she had rehearsed again and again in her mind —her mother had family in Freiburg, perhaps she might go to them instead of burdening Cord while he was still adjusting to managing the tavern—but had scarce drawn breath before he was throwing on his coat and striding out into the noisy bustle of the Fischerhalde, crowded with boats and nets and river, and up the steep street to St. Stephan’s.

Banns were called. Congratulations given. Ring on her finger.

Just the two of us now.

The first of the babies, a boy, came at summer’s end the year Junia turned seventeen. Mewling and screeching, red-faced and miserable. Cord, intent on running the Juniper Tree in a manner as different to his father’s as possible, had taken to drinking till all hours with his patrons, sleeping till midday. Keep him quiet, Junia. Clout needs changing, Junia. Latch it to your tit, Junia. And she did. She kept and changed and latched, and latched and changed and kept, until there was no telling where Junia began and the tiny, tender-sweet limbs ended. Perhaps it would have been easier had she loved the boy. As it was, he was just another of her many chores, the only difference being that, unlike a newly scrubbed floor or freshly made bed, there was never an end to the tending of him. Occasionally Cord took the baby from her and strutted him about the tavern, boasting. Happiest man in Breisach, he said. Apple of my eye. Hear, hear, the patrons cried. Roar and clink, splash and splatter. More for Junia to clean later, she supposed as she bent before the enormous stone oven, scrubbing out its belly. The warmth, the dark, was oddly inviting. What if she were to crawl inside and close the door behind her? Would Cord ever find her? Would the baby cry? Or would she simply sleep and sleep forevermore, cradled in a bed of soft, warm ash?

Sometimes, in the quiet of the mornings or before the evening rush, Junia strapped the baby to her chest and climbed the winding streets to the old monastery. The noise of Breisach—the rumble of carts and horses, the flurry of the Marktplatz and the fortress—faded as she entered the gates. She slipped off her shoes and walked barefoot across the neat lawns, dotted with statues and fountains, the occasional monk or two, until the gardens opened before her, cool and green. All were carefully ordered: herbs for the kitchen—rosemary, sage and fennel. Plants of healing—lavender, self-heal and restharrow. One garden existed for its beauty alone—rose, foxglove and larkspur—while another, for reasons of science and learning, bloomed with witches’ weeds: wolfsbane, hemlock and nightshade. An overgrown cloister led to an orchard, wild and thick as a forest. Life abounded there, but also death. Headstones were scattered throughout, the monks beneath them laying in eternal rest as they nourished the apple and cherry trees growing above.

A stone bench sat at the orchard’s southeastern edge. Sitting there, so high and quiet, Junia could see the outer defenses far below, bristling with artillery. Breisach was a fortress city guarding the river Rhine, an artery in the mass of veins and fleshy undulations that made up the Empire. Separating France and Württemberg, the river was the primary route into the Spanish Netherlands, the Habsburg emperor’s ally. Junia’s gaze followed the line of water as it snaked south toward Freiburg. To the west, it branched into a vast and glittering marsh which, pocked with patches of forest and a village or two, rolled toward the hill they called the Emperor’s Seat. And, beyond them all, the dark, beckoning curves of the Schwarzwald.

Sitting there, watching the birds as they flew from tower to spire, from wall to sky, Junia’s shoulders ached with longing. Let me fly, too. She prayed for a means to escape Breisach, its walls and its loneliness. Or, if that could not be, she prayed for a life without Cord in it. More and more the running of the tavern was falling into Junia’s hands. She was the one who met with the suppliers now, who haggled over the prices of wine and pork, who promised payment while Cord slept his days away. If not for her, the tavern would have been filthy, rotting beneath a crust of grime and sticky, nameless fluids. If not for her, the suppliers, demanding payment, would have ceased to sell their produce to them at all. Cord was no help, no comfort. He was a sweaty presence in the dark when she longed for sleep. Hot breath at her ear, a rough hand pushing her face into the blankets. She prayed for the Evil One, who had stolen her cousin-husband’s body, and, in a way, her own, to leave. And if that was not possible, she prayed for Cord to lose himself in drink and stumble over the edge of the Fischerhalde into the Rhine. Long fucking way down. She prayed for rest and for freedom, too. But she didn’t get any, and she didn’t get any.

“You bake well, Junia,”Cord tells her one day.“Might be you should make more than just bread and Knöpfle. I’m going to let the cook go—we can no longer afford her. Someone will need to make the dinners, bake the sweets. Could be you?”

“Haven’t I enough to do already?”

Stupid thing to say. The Evil One is wearing Cord’s skin more and more these days. As though proving her right, his meaty hand flicks toward her with surprising speed, cracking her nose. Pain explodes. Three drops of blood, dark against the paleness of the linen, spatter her apron.

She stares at them, removed from the pain somehow, seized by a terrible knowing.

Another babe on the way.

Sure enough, another child is born to Junia and the Evil One. A girl this time, not that it matters. Can’t a man get some sleep, Junia? Where’s my fucking dinner, Junia? Clouts need washing again, Junia. The Evil One fills her husband’s form more and more. He grows angry over the slightest of things, pushing Junia from one corner of the kitchen to the other. Slapping her here, cuffing her there. The presence of the two children does little to ease Junia’s misery. She knows she should love them, has watched other young mothers with their babes—the kisses, the smiles, the looks of unbridled devotion—and wills her heart to feel the same. It remains steadfastly indifferent.

And Cord, it turns out, is doing more than just drinking with his customers. Turns out he owes coin, and plenty of it, not only to his suppliers, but his patrons, too. He has rolled so many bones he can hardly keep track of what he owes. Turns out Junia will be the one to help pay it all back.

Make the dinners, bake the sweets.

The whispers arrive first. They drift downriver, eddy among Breisach’s fishing boats, then ripple up its steeply cobbled streets. They grow louder, inking themselves on broadsheets, flying, spittle-drenched, from the mouths of priests during their sermons: the Protestant general Bernard of Saxe-Weimar has sold his soul to the French. Twelve thousand foot soldiers and six thousand cavalrymen, plus artillery, are at his disposal. He means to conquer the Rhineland, carve a new territory for himself.

Fear, so strong you can smell it in the streets. If the Rhineland was a cellar, Breisach would be its finest, silkiest wine.

Saxe-Weimar takes the forest towns first. Waldshut, Säckingen and Laufenburg. Rheinfelden is besieged and lost in a crushing Imperial defeat. Then Rötteln and Freiburg fall.

The people of Breisach feel the moment the gaze of the Protestant general settles hungrily upon them.

“He has something to prove,” Cord says at the supper table, “after what happened at Nördlingen. Fucking disaster. Twelve thousand men dead on the field. His own horse shot out from under him. It was only luck and those enormous balls of his that allowed him to escape at all. If he wants Breisach, he will do everything in his power to make it his. His reputation—or what’s left of it—depends upon it.”

“But Breisach is the key to the Empire,” Junia’s son says. He is thirteen now, tall and broad-shouldered like Cord. Apple of his father’s eye. “The emperor cannot let it fall.”

“He can’t,” Cord agrees, sopping up the sauce from his spätzle with a heel of bread. “Breisach lost, everything lost.”

Unease settles over Junia, as if a bad storm were coming. Life is hard enough without soldiers laying siege to the city, too. Isn’t she already salvaging the wreck Cord is making of the tavern? Cooking for its—increasingly disreputable—customers? Caring for the children, who, though growing rapidly—the girl is nine years old—still seem to claw at her all day with their wants and hungers and needs? Cord does the same at night, and she suspects that yet another babe is stubbornly—stupidly—clinging to the inside of her womb. She ladles more food onto Cord’s emptying plate and sits down wearily. Breisach lost, everything lost. That’s what they say at the emperor’s court in faraway Vienna. As if war hasn’t raged for twenty years, butchering cities like Breisach. Fire and famine, plague and ruin. They are fools, those Habsburg nobles in their finery. Everything was lost long ago.

Something warm and soft brushes against Junia’s ankle. The little cat is as devoted to her as ever. At night it sleeps beside her, its face close to hers. It is a tiny, purring comfort in the dark, a small piece of something for Junia alone.

“Breisach is impregnable,” Cord goes on. “She has never yielded her virginity. And she never shall.”

Junia’s son snickers at his father’s words—virginity—and his sister blushes. If the boy is a mirror image of Cord, then the girl is a reflection of Junia. She has the same blue eyes, the same fair hair. The same quiet, hopeless sorrow.

The cat pushes its head against Junia’s skirts. She reaches down, strokes its fur absently.

Breisach, with its command of the Rhine, its impressive fortifications and precious bridges, had ever lured enemies; it would not be the first time a Protestant general had set his sights on the city. The Swedes had tried to take it just five years before, failing when the Emperor’s Spanish allies came to relieve it after a siege that lasted three months. The crows had pecked at Swedish corpses for weeks after, dipping and wheeling over the marsh. Junia had watched them from the monastery orchard, envying them their dark-winged freedom.

“Let Saxe-Wiemer come,” Cord slurps around a mouthful of creamy noodles. “The Empire will not allow Breisach to fall. He will fail just as the Swedish did. I, for one, will enjoy watching it from our walls.”

Even so, he spends the last of their coin—as well as borrowing more—to buy up black-salted hams and bags of flour, as many as can be had. “The rich shall suffer along with the poor before this is over,” he tells Junia. “Let us have something to offer them in exchange for their beautiful tapestries, their silver plate and precious stones. We shall make our fortune if we play our cards right.”

Junia can barely contain her disgust. Last time the siege, and the hunger that came with it, had been hardest on Breisach’s poor. She had helped at the monastery when she could, picking fruit, plucking vegetables from the gardens, handing out bags of rationed flour to the poor who came, desperate and frightened, to the gates.

“There is power, and magic, in growing things,” one of the oldest monks had told her kindly. “The land protects those who care for it. Remember that, my child.”

She helps Cord move the supplies into the cellar alongside the casks of cherry-water and wine, schnapps and beer. Around them, the city stirs into readiness, its commander, Baron von Reinach, looking to its provisions, its walls and fortifications. Its precious well, the Radbrunnen, dug deep into the mountain below, will ensure the people have access to water. There is a garrison of three thousand soldiers and a hundred and fifty-two cannon at the Eckartsburg fortress, tasked with protecting the city.

It will hold.

Saxe-Weimar and his army arrive in early June. The citizens of Breisach hear the drums first—the heartbeat of an approaching beast. Junia is in the monastery orchard when the warning bells at the Eckartsburg burst into frantic life. She rises from the bench and runs to the walls. Far below, an enormous serpent is winding its slow curves—formed of men and horses, banners and wagons, artillery and oxen—out of the south. The morning sun glints on muskets and cannon, spurs, harness and pikes. Hold the fortress by all means possible was the order from Vienna. Hard to imagine obeying it as more and more soldiers come, endless and unrelenting: twelve thousand foot, six thousand cavalry. By evenfall, it is as though a city of canvas has surrounded Breisach, sprawling across the countryside, dotted with cookfires.

“Those Protestant bastards will not last,” Cord says confidently to his customers. “They might have coin in their purses now, but how will that help them in a week? A month? There will be nothing for them to buy, nowhere for them to spend it. They are camped in the mud like pigs. Time will work against them, along with its merry friends Hunger, Disease and Desertion. And if they do not end them, the emperor’s armies surely will!”

“They will!” Junia hears the customers slur over their tankards of beer and pots of cherry-water. “The emperor will not let Breisach fall!”

“We have provisions—”

“We have the Radbrunnen—”

“We have God on our side!”

But weeks pass, then two months. The Protestant army hauls in artillery, fortifying the surrounding countryside, digging a jagged line of communication between the French and Weimaranian camps. Hunger, Disease and Desertion are yet to make an appearance.

“We must wait,” Cord insists to his dwindling customers. Junia avoids the tavern rooms as much as possible now. The loyal patrons who enjoyed Uncle Johannes’s good food and wine, the pleasant surroundings, are long gone. The Juniper Tree is no better than the lowliest pothouse. There is fighting and dancing every night. Dice, and dark dealings. She has learned not to glance into shadowy corners. “The emperor will send aid.”

By August the cellar, like the rest of Breisach, is all but empty. The meats and cheeses are long gone, the flour dwindling. Cord has made a pretty penny raising prices, offering what few can now afford, but even he is relieved when an Imperial army of Bavarian mercenaries arrives and attempts to drive out the Protestant soldiers. They are beaten soundly back, the supplies and powder meant for the besieged city lost.

“They’ll be back,” Cord proclaims, helping himself to the last of the blutwurst Junia has scrounged from the cellar for supper. “The Empire cannot afford to let the city fall.”

Junia tries not to see the fear in her daughter’s eyes. “Eat, child,” she snaps, getting to her feet. “And help me with the dishes. Do you think we’ve time enough to sit about crying and worrying?” The little girl wipes away her tears, collecting her father and brother’s plates and bringing them obediently to the tub for Junia to wash. Junia does not miss the appraising look in her son’s eyes as he watches his sister. It reminds her of the way Cord once watched her. Bile rises in her throat.

Breisach holds its breath, watching the horizon, hoping that the Imperial army will return and try again to lift the siege, but the Bavarians do not come back.

Saxe-Weimar, meanwhile, orders no batteries, no trenches to be opened. He merely digs in and holds fast.

“What is he waiting for?” Junia whispers as she surveys the Protestant army from the orchard. Beside her, the old monk, her only friend besides her little cat, takes in the ruined countryside, his rheumy eyes filled with unbearable sadness.

“It is hunger that undoes a besieged city in the end,” he says quietly. “He’s waiting for us to starve.”

The summer drags on, the fear that has settled over Breisach ripening like wheat beneath the brutal sun, shimmering over the marshes and the Rhine. A silent, invisible enemy has wrapped its talons around the city.

Hunger.

The bloody skirmishes that punctuated the early weeks of the siege—daring sorties by the garrison to fight the enemy and gather supplies—happen less and less frequently now. There is no food coming in, and nothing to be done.

“We should close the tavern,” Junia tells Cord. “Save whatever food we have for ourselves. Who knows how long this will last? We must think of the children, Cord.”

“No,” Cord says. “We must find more food, that’s all.”

“There is none to be had!” she hisses. “I’ve been to the market every day—”

“Then we must look harder.”

Junia tries not to listen as Cord butchers the old cart horse in its stable. The gentle beast has served him and his father loyally, hauling casks of schnapps and sacks of flour to the Juniper Tree for more years than Junia can tell. When it is done and the carcass is hanging, enormous and bloody, in the cellar, he carries a haunch into the kitchen and hefts it onto the workbench. Junia, horror and sorrow warring in her heart, makes no move to touch it. The Evil One tilts his head toward the tavern rooms, a silent command to begin cooking for his customers. Junia, wiping away tears, obeys.

Horse, she soon discovers, is better boiled than roasted.

Summer gives way to autumn, and still Breisach suffers inside its walls. There is not a horse, donkey or mule to be seen alive, now. The hideous sounds of their slaughter have at last fallen silent.

“We should have closed the Tree, saved the horse meat for ourselves,” Junia says to Cord when he comes home empty-handed from the market. It is not safe for Junia to go there now. Not a week ago, a wealthy woman’s kitchen maid was beaten, her meager purchases stolen. “We have nothing.” Cord had made a staggering profit on the meals Junia had cooked with the horsemeat, but for what gain, in the end?

“Not nothing,” Cord says. He draws something from behind his back. Three scrawny cats, their soft bodies hanging limp from his fist.

Junia stares at the cats, then at her husband. The Evil One looks back.

“Where is your cat, Junia?” he asks.

The cat, Junia well knows, is sleeping upstairs, a puddle of shadows on her side of the bed. A creature of habit, it is where it is always is at this time of day. Cord knows this as well as she.

“Don’t, Cord,” she says. She loves that little animal. Loves its purring warmth, its beautiful green eyes. “Please, don’t.”

The Evil One says nothing.

She wonders if she can get to it before him. Eyes the narrow stair, Cord’s broad shoulders, the evil lurking beneath his skin.

He moves. She runs at him, catching at his arm, pulling him away from the stairs. He throws her off. Backhands her, sends her crashing into the table, scattering chairs as she hits the floor. Searing pain, a wrongness, deep in her belly. She stays down.

By the time she is on her feet again, it is done.

Cord barely glances at the blood on her skirts, the whiteness of her face, as he slaps four little bodies onto the workbench.

“We’ll open soon,” he says. “You’d best get started.”

She wonders if he will hit her again. Glances at the knife on the board. Cord, however, walks heavily from the kitchen. A moment later, she hears the thud of an empty tankard on damp wood. The gurgling of liquid filling it.

As Junia cuts and slices, breathing through the pain shattering her heart and womb, something else cracks inside her. She barely feels it. Barely feels it, as she bundles what remains of the tiny thing she has lost and buries it beneath the juniper tree.

It never had a chance.

Hunger, as the proverb says, is a fine cook. By the end of October there have been several more attempts by Imperial forces to liberate the city. All have failed. In the final assault, the Protestant general himself rode out beside his men. An eagle hovered in the air above him, an omen of impending victory, a sign of witchcraft, or both, depending on which whisper in the Marktplatz you chose to believe.

“Bernard of Saxe-Weimar will triumph, mark my words.”

“When all of this is over, he will be left with nothing but bones. . . .”

“Did you see that eagle? Only a witch could compel a wild creature to fly into battle like that.”

Junia cares little for the fate of the Protestant general. Witchcraft or no, she merely envies that eagle its beautiful, gold-brown wings.

Breisach is now empty of cats and dogs. Junia has cooked her fair share for the tavern’s patrons—or those with enough coin, at least—roasting the animals whole with herbs and spices. Cord tells her approvingly that the thighs of the dogs she prepares are as tender as saddles of hare.

She cannot believe that the tavern remains open, that Cord is still beguiling wealthy customers with promises of tender meat and fine sauces. She waits for the city officials to appear on their doorstep, outraged and ordering them to close, but it does not happen. One quick look at the streets of Breisach and it is easy to see why. The city officials have more than enough—and, at the same time, never enough—on their plates.

Every garden, every tree and every plant in the city has been stripped bare. Even the weeds thrusting their fragile heads between the cobbles or beside doorways are gone. When Junia goes to the monastery, she finds its gardens have been looted. Every apple, every leaf taken. She finds the body of the old monk nearby. There is power, and magic, in growing things, he had once told her. The land protects those who care for it. She sees little power and protection here. The powerful ones have been and gone. They have taken what they wanted and protected no one but themselves.

“You old fool,” she murmurs, when she has buried him in the orchard. It feels more like a graveyard now, the monuments and death lanterns stark between the leafless trees. Shadows and stone, where once there had been something green and good.

At last Cord is forced to close the tavern doors. Even the rich cannot buy a decent meal in Breisach now; there is simply no food to be had. The people are eating animal hides, boiling, scouring and scraping each piece before roasting or grilling it like tripe. Animal skins have taken the place of vegetables and cuts of meat in the Marktplatz. A crone sells a bitter-tasting draught she swears will ward off hunger and heartache; she is carted off to the fortress prison for her troubles. Books and manuscripts are also being sold for eating, along with drum skins, harnesses and belts. All of this, of course, costs money. Cord, however, refuses to buy a thing. “We shall not squander our hard-won savings now,” he declares. “Not when the Emperor will send an army to lift the siege at any moment.”

So Junia boils straw and candle fat, grinds bones and nutshells to make limp, tasteless bread. Hunger kneads its bony fingers into her relentlessly, poking at her empty belly, gnawing at her thoughts. Dark whispers unravel in the narrow streets: people, the whispers say, have been carving and cooking the flesh of their newly dead relatives before they prepare them for burial. Children, mostly; the city’s young are suffering the most. The poorest of them have taken to hunting rats and mice in the streets. Junia has seen them clustered in ragged groups, cooking the animals over coals, skin and all, before wolfing them down. Fur, tail, foot—all provide nourishment. Though disgusted, Junia cannot blame them. However, when she sees her own daughter bending greedily over one of the tiny creatures, something in her tattered soul stirs. She rips the mouse away and throws it back onto the coals.

“But Mama,” the girl cries. “I’m so hungry!”

“We do not eat vermin,” Junia snaps, dragging the child back to the tavern. She looks staunchly ahead as she goes, hiding her tears and her rage.

All for a fucking river.

She leaves the girl in the kitchen and stumbles down the cellar stairs. Surely there is something left? A wrinkled apple or two? A stray jar of sauerkraut rolled beneath the lowest shelf? There is movement in the darkness behind her, a gasp, scuffling. Junia peers into the shadows. Her son, all fourteen years of him, is standing over a kneeling girl. His hand knotted in her hair, her face pressed to his—

“What in God’s name is happening here?” Junia demands.

“Calm yourself, Mother,” he says carelessly. He pushes the girl away, ties his breeches. “I promised her some food, that’s all. She’s more than happy to earn it.”

Junia pulls the girl to her feet. She is pale, her eyes large in her too-thin face.

“Go,” she tells her. “I will find something for you to eat. There’s no need—for this.”

“What the fuck are you doing?” her son demands as the girl scurries upstairs. “She—”

“This is my house,” Junia says, her voice death-quiet. “And you will not treat people so while you are within its walls.”

“It’s not your house,” he says. “It’s father’s.”

“And you think he will condone what you have done?”

The boy smirks.

Apple of his father’s eye.

He shoves past her, climbs the stairs. He is almost at the top when Junia reaches him. She wants only to make him stop, to make him see her. To take back some of the power she has given away and given away. Hunger, however, makes her clumsy. She trips on the stairs, sprawls. Her hands fly out, knocking at his ankles. He falls back, that height, those shoulders of his working against him. Down he goes, sudden and hard, his body jouncing on the stone steps, his head cracking on the flagged floor.

He doesn’t move again.

Alone in the darkness Junia thinks of the juniper tree. How it looked when it was thick with berries. The way the children used to help her pick them when they were very small. They were sweet creatures, then, the boy and the girl. When Junia baked they helped, licking the batter from spoons, spreading the workbench with flour. Sometimes, when her heart was soft enough, Junia bought ginger and cinnamon, honey and cloves. She did not love her children, it was true—she loved no one, couldn’t—but she took a secret, treacherous delight in baking for them, in seeing them peer blissfully over the trays, their button noses breathing the scent of warm gingerbread. Plump little hands, soft stubby fingers. If only the boy had stayed that way. If only Cord, and hunger, and the great sinfulness had not twisted him.

If only Junia’s tears, her rage, were content to remain in the darkness.

That evening, when Cord rises from his slumber and comes down for his supper, he pauses on the stairs, sniffing.

“Odd’s bod, Junia,” he says. “What is that wonderful smell?”

“It is blood soup,” Junia tells him.

“Blood soup?” He sits heavily at the table. “But where did you get the meat? The blood?”

Junia says nothing, only fills his plate with the rich, dark stew.

“Delicious,” Cord says, tasting his first mouthful. “And perfectly seasoned, too.”

Junia smiles. She thought of her son’s round baby face, his sweet toothless smile as she cooked the stew, and her tears fell into the pot. There was no need for salt.

“Give me some more,” Cord says.

Junia obeys. It seems the more Cord eats, the more he wants. She and her daughter, the latter’s face deathly pale and wet with tears, watch in silence as he eats and eats and eats, throwing the bones under the table. They ate their fill long before Cord rises, along with the girl from the cellar, who wiped her mouth with her sleeve, smearing the red-dark sauce across her lips, and thanked Junia before slipping out into the dusk.

“I must stop,” he says at last, “else there will be none left for my son.” He sucks on a bone. Part of a finger, Junia thinks distantly. “Where is he?”

She stares at him. All her livelong days, it’s been give and work, work and give. Scrub the floors, Junia. Bake more bread, Junia. Latch on to my cock, Junia.

She will give no more.

“He is dead,” she says. “And should you wish to remember him, you may look down your own throat.”

Cord’s face goes white. His daughter, sensing danger, hurries upstairs.

“But do not grieve, husband,” Junia continues blithely. “If this blood stew of mine is as delicious as you say, then perhaps we should open our doors to our customers tonight. We shall make a goodly profit.”

Cord is coming for her, eyes black with rage. He grabs Junia by the hair, throws her onto the stove. She catches herself before she burns her palms or knocks over the simmering pot of stew. He will kill her this time. She is sure of it. Part of her greets it warmly—an end to hunger and fear, to this appalling siege. Then she thinks of the girl upstairs. What will become of her if Junia leaves her here alone? Cord grabs for her, misses as Junia slides away.

“Fucking witch!”

Before she can move again he seizes the pot and hurls its contents in her face. Pain, blinding pain. Darkness and the burning crimson of her son’s blood.

Junia screams, clutches at her eyes.

Cord is almost upon her. She can hear his ragged breath, feel his pain and rage.

And yet Junia has rage enough of her own. Pain, too. She feels them coil within her, a serpent straining against her bones, her skin, eager for release. She lashes out, glimpses, despite her blurring, burning eyes, something nameless and dark leaching from her fingertips. It strikes Cord in the throat so hard that he flies backward, smashing into the wall. Crockery falls from the shelves above him, splintering upon his shoulders, his head, his thighs. A garner of flour crashes beside him, dusting the air with winter.

Power and protection, indeed.

Cord is gaping at her. “What in God’s name was that?”

The shock on his face, the drivel of bloody snot clumping from his nose, the fear in his eyes drive Junia’s pain away.

“That,” she says, “was a fucking delight.”

She reaches for the pot and scoops out what’s left with one hand. Licks at the thick, sour liquid, chews the tender meat with relish.

It seems the Evil One has found a home inside her, too.

By November, the bodies of the city’s living have become the graves of the dead.

When a captured Protestant soldier dies in the fortress, the prisoners in the adjoining cells tear holes in the walls—and then his body. Corpses have been stolen from the burying grounds so often that guards have been stationed there at night. Junia has glimpsed them, their shadows wavering beneath the death lanterns as they keep watch.

Children are going missing, too, the tales told in grim whispers on the winding, wintery streets. Soldiers promised a baker’s son a piece of bread if he would go with them to the barracks. Once they had him there, they butchered him.

She warns her daughter of the danger as she ladles her a bowl of fresh blood soup.

“Where is Papa?” the girl asks.

“Eat your soup,” Junia says. She ignores the salty tears running down her daughter’s cheeks and takes a mouthful, biting back a groan as the rich flavor melts in her mouth. Cord was a good father, a good husband, after all.

The girl’s belly grumbles. She wipes away her tears and takes a tentative mouthful, then another, the spoon hastening as disgust fades and the will to survive takes its place.

Junia knows the feeling well.

Cord keeps them alive as winter arrives in earnest. More children disappear—seven from the Fischerhalde alone. Junia keeps a watchful eye on the girl, forbids her to step foot near the fortress, the barracks.

It makes no difference. The girl vanishes one snowy morning in early December. Junia searches the city, barely feeling the cold. Every closed shutter, every smoking chimney, taunts her. She staggers to a stop near St. Stephan’s. Glimpses herself in a grimy window. She is thirty years old, yet she looks like a crone: hollow cheeks scarred by fire and blood, damaged eyes weeping, golden hair faded to grey.

That night the juniper tree loses its leaves and berries, its branches stark against the winter sky. By morning it is nothing more than a gnarled memory.

Junia no longer watches the armies from the monastery walls. She calls her little cat back to her with pain, slicing at her skin and letting the blood fall at the foot of the juniper tree. Waits in the moonlight as it scrabbles its way up through root and earth and snow. Bones push through its tattered fur. Grave-dirt stains its breath. Yet it curls beside Junia at night and follows her everywhere by day: along the Fischerhalde, or through the empty Marktplatz. People stop and stare as Junia and the not-dead cat pass. They whisper of witchery and crook their fingers in the sign against evil.

Junia pays them no heed. Hunger, however, is harder to ignore. Luckily, there are still children in the Fischerhalde. She visits the burying ground with her little cat, draws the shadows around them both as she digs for bones. Grinds them into powder and bakes—with the last scatterings of ginger and cinnamon, the newly tattered magic rising within her—something treacherous and secret.

Plump little hands, soft stubby fingers.

No salt needed.

Nothing sweeter.

The Imperial fortress of Breisach surrendered on the seventeenth day of December in the year of our Lord 1638. The city commander, Baron von Reinach, was permitted to leave honorably, bearing his colors and two cannon. He retreated to Strasbourg, four hundred soldiers—all that remained of Breisach’s garrison—and countless citizens with him. If you were watching the column march from the city gates, you might have been struck by the vivid colors of the banners rippling above, the glimmer of the winter sun upon harness and spur. You might have felt the beat of the drums, of booted feet and ironshod hooves. And, if you looked very closely, you might have seen a small white bird, wings outstretched, breezing above the defeated soldiers. You might have watched it turn south, toward the beckoning curves of the Schwarzwald.

A small white bird, its beak stained crimson.

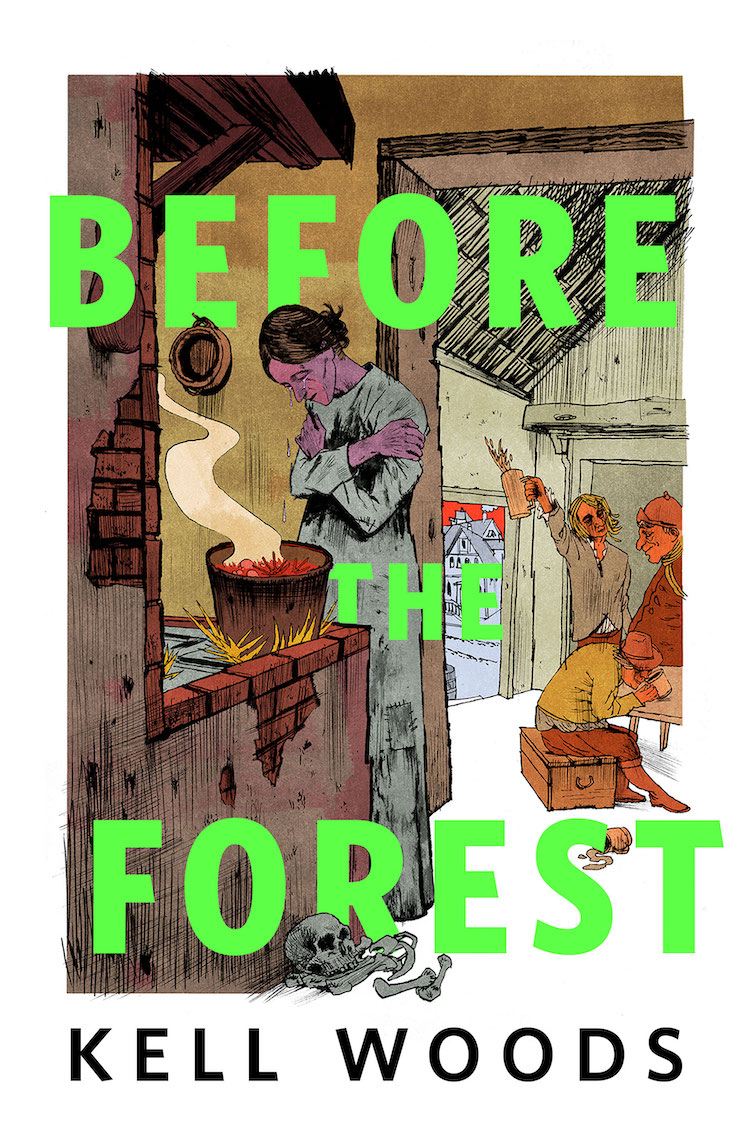

“Before the Forest” copyright © 2024 by Kell Woods

Art copyright © 2024 by Matt Rota

Buy the Book

After the Forest

Buy the Book

Before the Forest

Hauntingly brilliant. The way the siege was described and how the city is gradually pushed to its breaking point is horrifying. Junia slowly loses everything starting with her freedom, ending with her sanity as her mind snaps. Where before she tried to be good in a cruel world in the end she becomes cruel herself to survive.